Operation Eagle Claw: The Iran Hostage Rescue Attempt That Changed US Special Ops

The Genesis of a Crisis: Tehran 1979

To understand the desperate measures that led to the failed hostage rescue in Iran, one must first grasp the volatile political climate in Iran in the late 1970s. The Iranian Revolution, which culminated in the overthrow of the U.S.-backed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the establishment of an Islamic Republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, fundamentally altered the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. Anti-American sentiment, fueled by decades of perceived Western interference and support for the Shah's autocratic rule, reached a fever pitch.The Storming of the Embassy

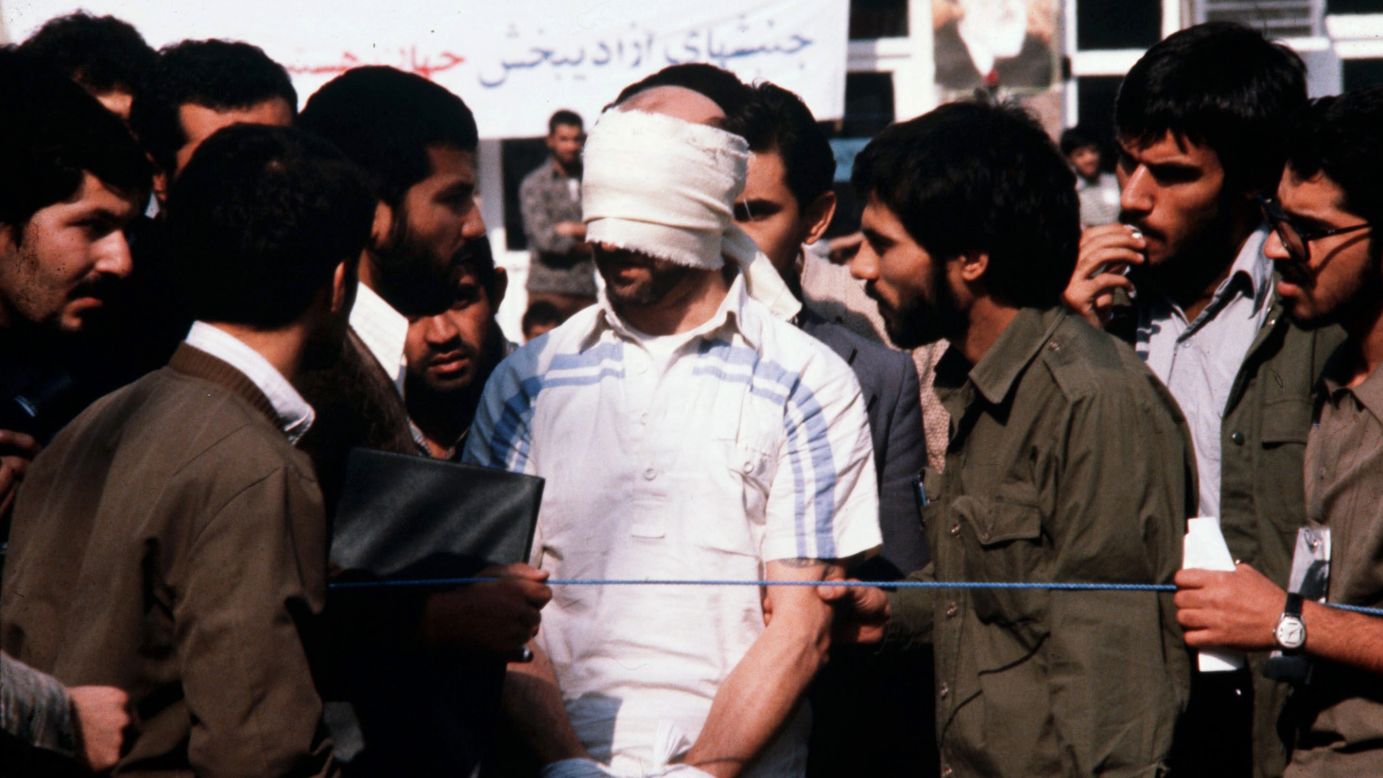

On November 4, 1979, a seismic event occurred that would set the stage for the crisis. Approximately 3,000 militant Iranian students, driven by revolutionary fervor and a deep-seated resentment, scaled the walls of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. They swiftly overwhelmed the security guards, breaching the sanctity of diplomatic territory and taking 66 U.S. citizens hostage. This act was not merely a protest; it was a direct challenge to American sovereignty and a clear signal of the new regime's defiance. The students demanded the return of the Shah, who was then in the United States for medical treatment, to face trial in Iran. This demand, coupled with calls for the end of Western influence, became the central sticking point in the ensuing diplomatic standoff.The Diplomatic Deadlock

The immediate aftermath of the embassy takeover saw a flurry of diplomatic efforts, but they proved futile. The Iranian government, under Khomeini's spiritual guidance, refused to negotiate directly with the United States on terms acceptable to Washington. The initial release of 13 hostages (women and African Americans) on November 19 and 20, 1979, offered a glimmer of hope, but the remaining 53 hostages faced an uncertain future, held captive under harsh conditions. For five long months, negotiations faltered, covert operations were explored, and the crisis deepened. The United States found itself in an unprecedented predicament: its diplomats and citizens were held by a sovereign nation, yet diplomatic channels were effectively closed. The mood in Washington grew increasingly tense, and the American public's patience wore thin, creating an immense political burden on President Jimmy Carter.The Imperative for Rescue: Why Operation Eagle Claw?

As the hostage crisis dragged on, President Carter faced mounting pressure from within his administration and from the American public. The diplomatic avenues had been exhausted, and the psychological toll on the hostages and their families was immense. The decision to attempt a military rescue, though fraught with risk, became increasingly inevitable. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) were initially caught by surprise by the President's decision, highlighting the lack of a pre-existing, robust special operations capability designed for such complex, multi-faceted missions. The underlying rationale for Operation Eagle Claw was multifaceted. Firstly, the humanitarian aspect was paramount: freeing the American citizens held against their will. Secondly, the United States' international credibility was at stake. The inability to secure the release of its own diplomats was perceived as a sign of weakness on the global stage. Thirdly, there was a growing concern for the hostages' safety, particularly as the political climate in Iran remained unpredictable. By the eighth day of the crisis, it was clear that a conventional diplomatic solution was unlikely. The "first realistic capability to successfully accomplish the rescue of the hostages was reached at the end of March" 1980, after months of meticulous, top-secret planning. This window of opportunity, combined with the desperate circumstances, pushed President Carter to greenlight the daring, yet dangerous, mission. This was not just about rescuing individuals; it was about restoring American honor and demonstrating resolve.The Anatomy of a Secret Mission: Planning Eagle Claw

Operation Eagle Claw was an undertaking of unprecedented complexity for its time. The mission required the seamless integration of various military branches – Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps – each with their specialized assets and personnel. The overarching requirement for success was absolute operational security (OPSEC), meaning every detail had to remain a closely guarded secret to prevent detection by Iranian forces.Assembling the Pieces: Personnel and Equipment

The planning for the failed hostage rescue in Iran was a monumental logistical and strategic challenge. Intelligence sources in Iran had largely disappeared after the revolution, making on-the-ground reconnaissance extremely difficult. The United States also lacked bases and other resources in the immediate area, necessitating a long-range, multi-stage approach. The mission called for an elite force, primarily from the newly formed Delta Force, supported by Army Rangers, Air Force combat controllers, and Marine Corps helicopter pilots. The equipment was equally diverse and crucial. Eight RH-53D Sea Stallion helicopters, flown by Marine Corps pilots, were chosen for their heavy-lift capability and range. These were to be supported by C-130 transport aircraft, which would carry fuel, equipment, and the ground assault force. The plan was intricate, involving multiple phases and relying on precise timing and coordination. People and equipment were called on to perform at the upper limits of human capacity and equipment capability, pushing the boundaries of what was then considered possible for a joint special operations mission.The Desert One Staging Point

The operational plan centered around a remote staging area deep within the Iranian desert, code-named "Desert One." This desolate strip of road in the South Khorasan province was to be the critical link in the rescue chain. On the night of April 1, 1980, two CIA officers, in a clandestine reconnaissance flight, landed Major John T. Carney, an Air Force combat controller, on this small strip. His mission was to verify its suitability as a forward operating base. The plan was for the C-130s to fly into Desert One under the cover of darkness, carrying the ground assault team and vital supplies, including fuel for the helicopters. Simultaneously, the eight RH-53D helicopters would fly from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz in the Arabian Sea to Desert One. Here, they would refuel, pick up the Delta Force operators, and then proceed to a hidden location closer to Tehran. The next night, the ground team would infiltrate the embassy, rescue the hostages, and transport them to a nearby airfield for extraction by C-130s, with the helicopters providing support and diversion. The complexity was staggering, and the margin for error was virtually non-existent.The Fateful Night: April 24, 1980

The stage was set for the daring rescue. On April 24, 1980, the mission, ordered by US President Jimmy Carter, was finally launched. The C-130 transport aircraft departed from Masirah Island off the coast of Oman, making their way silently towards Desert One. The helicopters, meanwhile, lifted off from the USS Nimitz, embarking on their long, perilous journey across the Arabian Sea and into Iranian airspace. The element of surprise was paramount, and the entire operation was shrouded in absolute secrecy. As the helicopters flew deeper into Iran, they encountered unexpected and severe weather conditions – a phenomenon known as a *haboob*, or dust storm. Visibility dropped to near zero, forcing the pilots to fly at extremely low altitudes, relying on instruments and sheer skill. This unforeseen natural obstacle immediately began to unravel the meticulously crafted plan. One helicopter was forced to turn back dueating to a cracked rotor blade, unable to proceed safely. Another helicopter, disoriented by the dust and darkness, landed far off course and was rendered unusable. The mission was already losing critical assets before even reaching the rendezvous point.Catastrophe in the Desert: The "Fireball" Incident

The remaining helicopters eventually arrived at Desert One, but not without further complications. Of the eight helicopters that started, only six were operational upon arrival. The plan required a minimum of six operational helicopters to transport the ground force and the anticipated number of hostages. With one helicopter already lost en route and another experiencing hydraulic issues after landing, the number of mission-capable helicopters dwindled to five. This was below the critical threshold for the mission to proceed safely and effectively. The ground commander, Colonel Charles Beckwith, faced an impossible decision. With insufficient helicopters, the mission to rescue the 52 embassy staff held captive could not be executed as planned. The order was given to abort the mission. As the forces prepared to withdraw, disaster struck. In the chaotic darkness of the desert, one of the RH-53D helicopters, attempting to reposition for refueling, collided with a C-130 transport aircraft. The impact resulted in a massive explosion – "the fireball in the Iranian desert." Eight servicemen were killed in the fiery crash, and the remaining forces were forced to hastily evacuate, leaving behind the wreckage, equipment, and the bodies of their fallen comrades. It was a catastrophic end to what had been a desperate and complex endeavor. The failed attempt to rescue the American hostages from Iran 40 years ago left a deep scar.The Aftermath and Announcement: Carter's Sobering News

In the early hours of April 25, 1980, President Jimmy Carter made a sober announcement to the nation. He informed the American people that the military forces rescue attempt of the 52 staff held hostage at the American embassy had been aborted due to mechanical failures and the tragic accident. The news sent shockwaves across the United States and internationally. It was an indelible image of American military failure, a public acknowledgment of a mission that had ended in disaster, with servicemen dead and no hostages rescued. The immediate aftermath was one of profound disappointment and grief. The wreckage of the disastrous attempt, including the charred remains of the aircraft and helicopters, was quickly discovered by Iranian forces, providing undeniable proof of the secret operation. The Iranian government used the incident as propaganda, further solidifying their anti-American stance. For the United States, it was a moment of national humiliation, raising serious questions about military preparedness, inter-service cooperation, and intelligence capabilities. The remaining 53 hostages, however, had to wait out more months of uncertainty, their fate still hanging in the balance. They were eventually released on January 20, 1981, the day Ronald Reagan was inaugurated as president, ending 444 days of captivity.Enduring Lessons: The Legacy of a Failed Hostage Rescue in Iran

While Operation Eagle Claw was a profound military failure in its immediate objective – the rescue of the hostages – it paradoxically became one of the most successful failures in U.S. military history in terms of its long-term impact. The mission highlighted glaring deficiencies within the U.S. military command structure, particularly the lack of jointness and interoperability between different service branches when conducting complex special operations. The separate command chains, equipment, and training methodologies proved to be significant obstacles. Significant lessons were learned from Operation Eagle Claw, the 1980 Iran hostage rescue attempt. It became a catalyst for radical reform within the U.S. Department of Defense. The incident underscored the urgent need for a unified command structure for special operations, improved joint training, planning, and equipment standardization. The realization that such missions required a dedicated, integrated force capable of operating seamlessly across all domains became undeniable.The Birth of SOCOM: A Unified Command

Perhaps the most significant and lasting legacy of Operation Eagle Claw was the creation of the United States Special Operations Command (SOCOM). Prior to 1980, special operations forces were fragmented, existing within their respective service branches with little centralized coordination. The failures at Desert One, particularly the inter-service communication and equipment issues, served as a powerful impetus for change. The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986, heavily influenced by the lessons of Eagle Claw, mandated the establishment of a unified command for special operations. This led directly to the formation of SOCOM in 1987. SOCOM was designed to overcome the very deficiencies that plagued the 1980 mission. It brought together Army Green Berets, Rangers, Navy SEALs, Air Force Special Operations, and Marine Raiders under a single command, fostering joint training, developing specialized equipment, and creating integrated operational plans. This unified structure ensured that future special operations, whether counter-terrorism, direct action, or hostage rescue, would be conducted with a level of coordination and expertise previously unimaginable. None of the successes of modern U.S. special operations would have been possible if it weren’t for a failed mission in 1980 that forced the U.S. military to fundamentally rethink its approach.A Difficult Legacy: Commemoration and Reflection

Forty years have passed since the failed hostage rescue in Iran, yet its memory remains vivid for those involved and for the nation. It's 40 years, yes, and it's something you never forget. The veterans of the failed Iran hostage rescue mission gather periodically, as they did for the 30th anniversary at a hotel in Arlington, VA, to commemorate what they call "the most successful military failure in U.S. history." This paradoxical description reflects the profound impact the mission had on shaping the future of American special operations. The lessons learned from Operation Eagle Claw continue to inform military doctrine, training, and equipment development. The emphasis on OPSEC, the need for robust intelligence, the importance of adaptable planning, and the absolute necessity of jointness are all direct consequences of that fateful night in the Iranian desert. The sacrifice of the eight servicemen who perished, and the ordeal of the hostages, were not in vain. Their story is a testament to the courage of those who undertake the most dangerous missions and a stark reminder that even in failure, there can be profound lessons that lead to future strength and capability. The legacy of this failed hostage rescue in Iran is not just one of tragedy, but also of transformation, forging a more capable and integrated special operations force for the United States. The story of Operation Eagle Claw is a complex tapestry of courage, ambition, unforeseen challenges, and ultimately, a painful but transformative failure. It reminds us that history is not just a collection of triumphs, but also of critical moments of learning from adversity. What are your thoughts on this pivotal event in U.S. military history? Share your reflections in the comments below, or explore other articles on our site detailing significant moments in special operations history.- The Incredible Lou Ferrigno Jr Rise Of A Fitness Icon

- Pinay Flix Stream And Download The Best Pinay Movies And Tv Shows

- Discover The Exclusive Content Of Briialexia On Onlyfans

- The Renowned Actor Michael Kitchen A Master Of Stage And Screen

- Ultimate Destination For Hindi Movies At Hindimoviesorg

Iran Hostage Crisis Fast Facts - CNN

1979 Iran hostage crisis | CNN

40 Years After Hostage Crisis, Iran Remains Hotbed of Terrorism > U.S